A Spoonful of Olive Oil

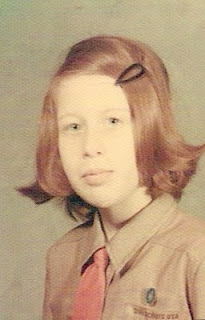

When I was eight, I rifled through glove compartments looking for nothing, really; read but didn’t quite understand the popular and erotic

novel, The Story of O, that my father

had buried away from prying eyes on the bottom shelf of the kitchen cabinets; discovered

medical papers stashed in a kitchen drawer noting various and sundry family

medical conditions including cavities, water on the knee, and a miscarriage; found

boxes of books including an ancient edition of The Wizard of Oz outside of our building and lugged them home; failed

the one question that my grandmother posed from an I.Q. test and never got over

it; decided that the Rorschach test, also administered by my grandmother, was just

a series of messy and misguided inkblots; and chopped off the hair of my Barbie

dolls. I wondered when I would start sprouting and wearing a training bra; purchased

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

thinking it was a medical book and was astonished at the stories of Native

Americans; read and re-read a large hardcover book for kids called Tell Me Why which I still have; wrote

obsessively using our class vocabulary words in essays; talked to everyone in

sight; defended my red hair when classmates tugged at it and called it a wig; and

couldn’t wait to move into my own apartment. I was on my way. To what, I didn’t

know.

Like a sharp detective, I sifted through ordinary objects

and conversations, both conspicuous and ephemeral, and analyzed them for clues,

signs, and hints as I searched for answers as to how the world worked, how

people felt and just well, why. The whys were inexhaustible as I searched for

meaning and purpose in things that were often none of my business. Finding my

mother’s birth control pills was none of my business but she stored them, like

many other items, in kitchen cabinets in our apartment in Brooklyn. From can

openers to candles, report cards, apartment leases, prescriptions, greeting

cards, a small bottle of olive oil used for medicinal purposes, glue, books, birthday

party hats, hammers, nails, eyeglass prescriptions and cases, dishes, pots and

pans, cleaning supplies, and cookies, the cabinets presented an ever changing

adventure of possibilities. When I wasn’t busy typing something, I poked

through the cabinets to see if something new had been added or moved. And when

I moved outside to the front seat of the car next to my father and grandmother,

I wrestled with the demons of glove compartments. A good day was finding a half

eaten Hershey’s bar or one of those accordion folded rain hats with the union

label that wasn’t there the day before.

I read somewhere that eight is the age where kids identify

themselves as athletic or not. As the person chosen last or close to it on every

playground team—let’s face it, dirt bomb throwing skills were not highly

prized—when

it was my turn to lead the pack, I picked the kids who were in the same predicament

that I was in. Then we were first. Leaving sporting games to others more

graceful, I turned to reading everything, from vaccination documents to letters

and bills, cereal boxes, novels, mysteries, and biographies. It was no wonder I

needed glasses. And still do.

Perhaps to see where we were heading, my Greek grandmother,

who worked for a psychologist after my grandfather died when I was three,

administered versions of I.Q. and Rorschach tests pilfered from the office. I

remember one question, which my younger brother, of course, answered swiftly and

correctly.

What would you do if

you found a stamped, sealed letter in an envelope with an address on it lying

on the ground?

“Put it in the nearest mailbox,” my brother replied.

I was certain that my answer was correct and jumped in.

“Open it up to see what’s inside!” I replied, as if we

should all know better.

Well. Wouldn’t you want to know what the mysterious contents

were? The correct answer was: Drop it in the mailbox.

My grandmother muttered something and moved on to the

Rorschach test, holding up an image of a black inkblot on heavy paper. The answer somehow determined your emotional

functioning, whatever that meant.

“It looks like a man in a hat,” my brother announced, or

something to this effect.

My grandmother beamed.

I turned my head sideways.

“Well,” I announced,

“It looks like ink that spilled on the paper. How can you possibly tell what it

is?”

My grandmother lost her beaming look. “God help your

grandmother,” she muttered in Greek, something I heard quite often. And that

was the end of any further testing in our house.

Books were everywhere, from the bookcase in the bedroom I

shared with my sister in the Linden Houses, to hallway closets, and the kitchen

cabinets. Almost all of them belonged to my father who collected thick, hardback

volumes of literature ranging from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Gertrude Stein

to the writings of Aristotle and Plato. We stacked them as high as we could to

build forts and added blankets over the top and hid underneath with children’s

books and flashlights to read. These days people buy prefabricated playhouses. We

made them out of what we had.

Books seated on the shelves of kitchen cabinets included a

set of encyclopedias, which I read cover to cover, along with a few pots and

pans. That’s where I found The Story of O.

And only recently learned of its theme of bondage. Back then, I thought it was

a book about the story of the fifteenth letter in the alphabet. I do remember that

there was a great amount of detail in the writing, though. I sat on the smooth

and spotless linoleum under the kitchen light and read while the rest of the

family was busy doing something else. The slim paperback was a measure of my

father’s eclectic taste and wasn’t meant to be discovered. But it was. I never

told anyone. Until now.

Above the counter, a metal toaster sat on the corner next to

a coffee pot. The toaster and I were not friendly, dating back to my sinister

act of sticking a fork into it to extricate a piece of stuck toast. I received

an electric shock that made my arm tingle and vibrate and to this day, I keep

my distance from toasters, particularly with a fork in hand.

I remember Greek dolls from my grandmother’s adventures to Greece, Israel, Florida, and Jamaica and to other distance places we only read about,

sitting in the kitchen cabinets above the sink. And that periwinkle colored candle

made in the third grade from a milk carton form. A box of sugar and container of

salt and some dishes added a bit of flavor to the display. Not much food,

though. The freezer was filled with frozen dinners and their individual

compartments of crystallized beef, chicken, potatoes, vegetables, and cake. That

bottle of olive oil lurked on the sidelines.

|

| This ancient Greek calyx was used for storing olive oil, long before it made its way to our Brooklyn apartment. |

My grandmother and her family brought the soothing tradition

of olive oil from the old country of Janina, Greece to the Lower East Side to

the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx and then to our home on Stanley Avenue in

Brooklyn. I never saw her use it, though. She used to fly up and down the Long

Island Expressway with her three grandkids in the car, singing “A Spoonful of Sugar Helps the Medicine Go Down” from the movie, Mary Poppins. I’m not sure she ever used the turn signal when

changing lanes but the wind blew my hair fearfully through the open

window as she sang with more gusto than Pavarotti. After a warning for the

thousandth time to get my hands out of the glove compartment and to leave the

dials on the radio alone, I looked across the lane as we passed old men in hats

with their hands clenched at the ten and two position. They stared straight

ahead and had no clue as to the performance on the road next to them. And

today, still, they are the slowest drivers anywhere. I guarantee this: Just

look for the hat.

I wish I could say it was a spoonful of sugar that cured

everything but in my house, the olive oil was our medicine, poured straight

from a small clear glass bottle that looked and tasted like lamp oil. And indeed, it had been used in lamps in

ancient Greece. It was presented at the first sign of illness.

Coughing? Itchy? Stomach upset? Earache? Headache? Cold?

Rash? Cramps? Out came the bottle. I asked:

“Why? Does this really work?” The answer was always the same: “Because.”

I can still feel the metal clank of the spoon against my front teeth as my

mother pumped a spoonful down my throat. Maybe my cough was not as raspy after

a tasting but the olive oil never did squelch my curiosity. Some things just

have to run their course.

|

| My kitchen cabinets today. |

And then the bottle returned to its place in the kitchen

cabinet, on the second shelf to the left of the sink. While the contents of the

cabinets were in constant rotation, the olive oil always remained stoically in

place.

Digging around in the kitchen and in glove compartments back

when I was eight, I found more questions than answers. And sometimes, there are

just no answers.

Even today, my own kitchen cabinets look different from my

friends and neighbors whose cabinets are filled with cookware, dishes, cans,

jars, bottles, and containers of food. Mine contain books, sewing supplies, vintage

Pyrex containers, knitting needles, three pots, decorated cigar boxes, a microphone,

papers, a wooden folk art sculpture of a sword swallower, and a metal cat. These

days, many glove compartments have been replaced by air bags. But old habits still

persist, and when I ride in the passenger seat of a car, I instinctively reach for

the latch of the glove compartment and find, sadly, that it’s no longer there.

.jpeg)

Comments