Death, Interrupted

In early March, an 87-year-old woman collapsed in a retirement home in Bakersfield, California. A staff member dialed 911, the

telephone number one calls to request help, and then she refused to offer

assistance to the dying woman. The emergency operator pleaded with her to give

CPR or to find another person who could. The woman died. Outraged members of

the media, medical ethicists, the public, and my friends debated the ethical

and moral responsibilities of helping to save a life while the woman's family said that

they were satisfied. Whatever this means.

It made me think back to two profound and complicated experiences

with elderly relatives, both in their nineties at the time, and the end of

their lives. One, tragically, was filled with forgotten forms that brought my

great-aunt back to life several times. The second, the passing of her sister, was interrupted

by her oldest grandchild who walked in during her very last hour.

Her building neighbors spoke Spanish, not Greek and Hebrew,

and they left the hallways perfumed with the scents of chicken and rice and

beans and fried fish. One by one or two by two, kosher butchers in the

Kingsbridge area closed, and she traveled further and further, sometimes taking

three buses for a round of hot dogs or chicken. Auntie Esther stayed her course

until she fell and broke her hip. She decided how she was going to live and

most stubbornly, how she would die.

Her building neighbors spoke Spanish, not Greek and Hebrew,

and they left the hallways perfumed with the scents of chicken and rice and

beans and fried fish. One by one or two by two, kosher butchers in the

Kingsbridge area closed, and she traveled further and further, sometimes taking

three buses for a round of hot dogs or chicken. Auntie Esther stayed her course

until she fell and broke her hip. She decided how she was going to live and

most stubbornly, how she would die.

Her neighbor telephoned me when she fell in her apartment and

luckily and thankfully, I happened to be home. Auntie Esther didn’t call the

generation between us. My mother was living in San Francisco and my aunt was

living in Co-Op City but I lived across the Fordham Bridge in upper Manhattan,

visiting every so often and telephoning to check in and say hello.

The second oldest of five Greek sisters, Auntie Esther had

been divorced once, married twice, and was now a widow. She had no children. Her oldest sister had

married a man in the film business, moved to Harlem, and died in the 1918 flu epidemic. The next was Stema, who died of breast cancer more than 20 years ago.

The youngest, Mollie, lived in a nursing home in Connecticut and didn’t

remember anyone, even though Auntie Esther insisted that she did. Mollie had

Alzheimer’s. My grandmother lived in another part of the Bronx and was in her

early eighties. So there I was.

Auntie Esther was 88 and I was 28. I knew almost nothing

about growing up and growing old, only that it happened to other people.

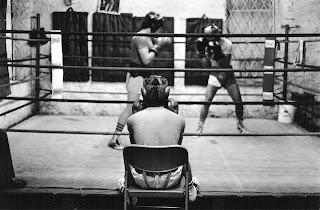

My writing and photography career was in full swing. But After

Auntie Esther’s telephone call which led her — and me — to two hospitals, a rehab

facility, and then home and back again, I went from deadlines, knockouts, hits,

champions, and home runs to hospital procedures, high blood pressure, elder care

law, diuretics, physical therapy, broken hips, pneumonia, wills, assisted

living, health insurance, Medicare, social services for the elderly, home

health care, feeding tubes, ventilators, social workers, living wills, nursing

homes, funeral homes, plain pine boxes.

The rest of my family remained in the background, a polite

way to say that they weren't interested or didn’t know how to be. Almost every member of my circle of friends, colleagues, and acquaintances hadn’t yet encountered aging and ill parents or grandparents

or to put it bluntly, the death of a family member. With perplexed sympathies and little support except

for “You’re doing a nice thing," it was a solitary endeavor of love and

obligation for almost six years. A geriatric caseworker filled some of my roles

for about a year, until Auntie Esther didn’t like her anymore.

While she recuperated from surgery, I attempted to organize, paint, and clean her apartment, and ensured that her medical paperwork

was in order. Auntie Esther knew what she wanted. When it was her time, she did

not wish to be resuscitated.

“No. Just let me go,” she said.

She repeated herself so that I would hear, even though she

was the one with the buzzing hearing aids.

She signed a DNR form in the hospital, which meant that if

any measures were needed to keep her alive, she didn’t want them.

After several years living at home, it became clear that

that she couldn’t stay in her apartment. Frustrated, fearful, and confused at

times, she made hysterical telephone calls to 911, telling the operator to get her out of

here. The very patient home health care worker we hired was drained, Auntie Esther was in and out of

the hospital, and I was on the verge of collapse. During her latest hospital

stay, I discovered how cruel it was to be in the hospital alone. A process

called “dumping” meant that a patient without family was transferred to a waiting

nursing home so that the bed was opened up for the next casualty of age. A

representative from the New York City Department for the Aging explained how it

worked. I telephoned Auntie Esther’s social worker at the hospital and demanded

an answer.

“Don’t I have a say in this?” I asked. “Why did no one call

me? My name is on the paperwork and I’ve been there to visit. This isn’t going

to happen.”

The social worker seemed taken aback, as if I were

ungrateful for her services. I called the New York Health and Hospitals

Corporation who called the hospital and well, it gave me an extra day or two. The

social worker, annoyed, offered two choices of nursing homes and I visited the original

one first. A room filled with elderly women wearing pink acrylic sweaters sat

lined up in front of a television that wasn’t turned out. The air smelled like

urine. I whispered to a man mopping the floors.

“Would you send your mother here?”

He shook his head.

Nursing home number two wasn’t far from where she lived. I

was running out of time before she would be discharged, and thankfully, it seemed much less depressing and with better services. Paperwork was filled

out and so was a DNR form.

Auntie Esther was now 94. She hated the nursing home, hated

her roommate, hated the food, and hated me. I was drained mentally and

physically from rounds of meetings and telephone calls, emptying and cleaning

her apartment, moving her in to the nursing home, traveling, negotiating, being yelled

out, bureaucracy, and paperwork while continuing to work as a journalist.

She was living in the nursing home for less than a year when

the telephone rang. She had been taken to the hospital. I asked about the DNR

form. No one could find it. I dutifully went in and filled out the paperwork with her again.

Auntie Esther was angrier than ever that her wishes had not been followed. I

shook my head. I had no answers.

I spoke with the nurse:

It should be in her chart. Was it a mistake? Did they lose her

paperwork? Was this the mistake of a newer employee? Auntie Esther continued to

yell, her hearing aids not picking up that I had nothing left but apologies. I

remember walking away out of frustration. Nothing could go right.

Several weeks later, the telephone rang again. Again, she

was resuscitated. I dutifully trudged to the nursing home, bracing for the

barrage.

“Why did you do this?” Auntie Esther screamed at me.

I shook my head. My parting mental photograph is of her sitting

in a wheelchair yelling at me as I retreated. The form was filled out again.

I was almost down for the count. And the phone rang again. She

was taken to the hospital. And resuscitated once again. Auntie Esther sat up in

the hospital bed with a large plastic tube in her mouth, her eyes unblinking in

anger. If she could have yelled at me, I’m sure she would have. It was like a

horror movie.

The doctor informed me that her kidneys were failing, and he

spoke about withholding food, what he could and couldn’t do. I made calls to

medical ethicists so that I could make a decision and it left me more

confused. I had no idea of what to do, of the capabilities of the human body,

what dignity she had left. It all seemed so unfair. And then the phone rang.

This time, she had her wish.

******

Auntie Esther’s younger sister was my grandmother, and she had a DNR form on file with her nursing home. My aunt, my mother’s sister, took responsibility for her care and moved her to Brooklyn to be closer to her. I visited Nonie several times a month, sitting with her in her room or in the hallway when she sat quietly with the others watching reruns of Zena, the Warrior Princess. Taking a deep breath, I would run into the nursing home, ready to greet her like when I was a kid and she arrived with shopping bags of food and gifts. She would practically topple over from my enthusiasm and endless questions, sighing, “God help your grandmother.” But she expected no less. I almost expected to see her like this once again.

“What do you think about?” I asked her during my visits, as we

sat together.

“What do you think?” she retorted. “I’m waiting to die.”

After these times, before I headed to the subway, I would

lock myself in the visitor’s ladies room and cry. But I learned to be careful.

Once, I accidentally pulled the emergency call string reaching for a wad of

toilet paper to dry my eyes. A kindly staff member checked to see what the

emergency was.

“Something in my eye,” I called out through the door.

And then one afternoon, it happened. Bursting into the room,

I called out “Nonie! It’s—“ I stopped. Shades were down, lights were off, and the air

was filled with the ghastly raspy sound from an Edgar Allen Poe short story. It

was ancient rattle of death.

Nonie lay in her bed, her eyes closed, and looked peaceful.

Touching her arms and smoothing her hair, I shook her gently by the shoulder. She didn’t

react. So this is what happens in nursing homes, I thought. They leave you to

die. Only I had interrupted the plan.

I called my aunt from the phone next to the bed and she instructed me to call the doctor on duty. The doctor said there wasn’t much

they could do. She didn’t seem too concerned. I panicked. Didn’t anyone care? I

asked her to call 911. What they could do, I didn’t know. The ambulance came.

And instead of dying alone and perhaps peacefully, we hauled off to the local

hospital in an ambulance, lights flashing and sirens blaring, hitting every bump like the

Cyclone at Coney Island. So dizzy was I after the ride that I thought that I, too, might

have to be admitted.

Nonie was wheeled into into the emergency room while I hung

onto walls and chairs until the dizziness subsided. Just as I began a

conversation with a doctor, the emergency room was cleared to make way for a prisoner

in handcuffs, wheeled in, an arrest from the local precinct.

I was moved into a waiting area for my safety.

And then she died.

There’s no morale to the stories here except that nothing

ever goes according to plan, including dying. With Auntie Esther, we diligently

filled out paperwork and instructions again and again and again. And with my grandmother,

all was going according to some plan, I suppose.

In the case of my great-aunt, DNR forms had clearly been

filled out and should have been followed. Auntie Esther was in agony. Perhaps

the motive for not finding the forms was more sinister: She was a paying

customer, so to speak, and every day of residence meant income for the nursing

home. But I don’t know this for sure.

And with my grandmother, the only thing that interrupted her exit from this world was me. But she would have expected that. She said that I never gave her any peace. Well, she was right. Even at the end.

And with my grandmother, the only thing that interrupted her exit from this world was me. But she would have expected that. She said that I never gave her any peace. Well, she was right. Even at the end.

Auntie Esther's life is chronicled in an essay, The Bronx is Burning while Nonie's is included in A Spoonful of Olive Oil, both on this blog.

.jpeg)

Comments